On the Occasion of Our 60th Anniversary

By David Hackett, Emeritus Professor

In his provocative book, The Soul of the American University, historian George Marsden argues that only a century ago, almost all state universities held compulsory chapel services, and some required Sunday church attendance. As late as the 1950s, it was not unusual for leading schools to refer to themselves as “Christian” institutions.

While chapel may not have been compulsory at the University of Florida, as recently as 1952, Baptist minister and University President J. Hillis Miller declared that “there are no walls between student religious centers and the University.” At Christmas time throughout much of the 1950s, Miller and his successor J. Wayne Reitz presided at a midnight service where they delivered a Christian message and blessing as students left for home for the holidays.

The decision to create a Department of Religion in 1946 was both a secularization from and a continuation of this earlier model of the “Christian University.” (Prior to 1946, the only public university with a department of religion was the University of Iowa which began its department in 1927. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill founded its department in 1947).

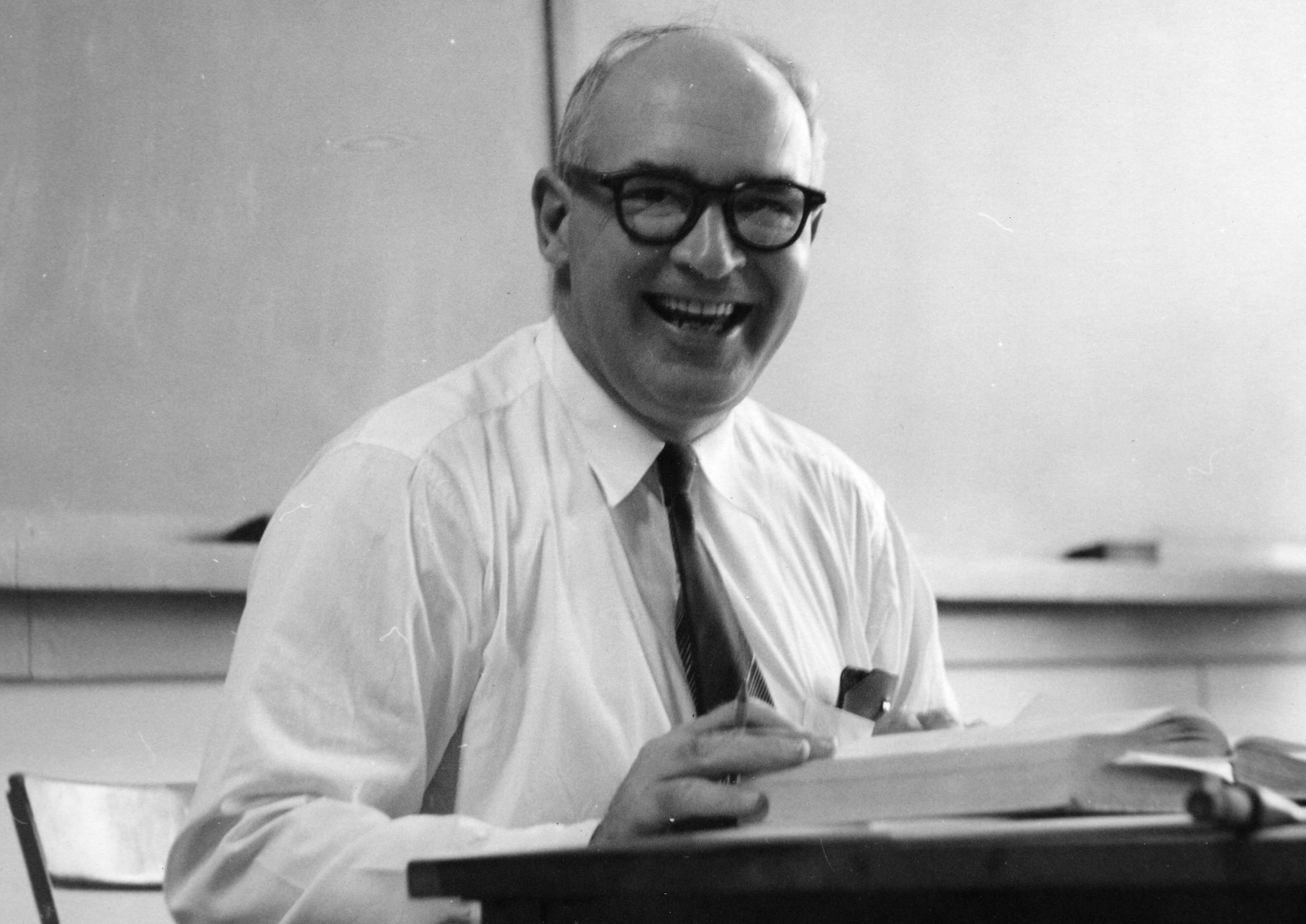

When Delton Scudder [pictured above] was hired to create the Department of Religion he was given two responsibilities: 1) to develop a curriculum in religion, and 2) to organize and develop student religious activities.

It wasn’t until the late 1960s that the religion department’s academic responsibilities became wholly separated from its ministerial duties. Throughout these early years, the department offices were set apart from other academic departments and placed close to student activities in the student union.Religion in Life Week

One impact of the Department upon the University during the 1950s and 1960s was its development of what became known as “Religion in Life Week.” During this “week,” normal University activities were altered so that all might participate.(014 Picture) In one broadside from this time period, Liston Pope from Yale Divinity School is to address the whole of the student body in the Florida Gym on the topic “Is Learning Enough,” and down at the bottom it states “All Classes Dismissed for the Convocation.” A typical Religion in Life Week began with Sunday services in the town’s various denominational churches and continued with large gatherings for addresses as well as smaller meetings in every academic department and residence hall throughout the University.

Through the eyes of today, we can see that these events were primarily Protestant, white, and male, reflecting the social make-up of the University until at least the late 1960s. Faculty from those days, however, will tell you that women were very much included in these events, both as organizers and speakers, as were Catholics and Jews. For the times, Religion in Life Week was a challenging, progressive experience where hot button issues of the day were debated and lead by the finest speakers. In 1951, the Syrian Orthodox Archbishop of Jerusalem gave a talk on the four Dead Sea Scrolls that he had just brought to the United States. In 1962, Victor Frankl held center stage with his address on “Man’s Search for Meaning.” William Sloan Coffin’s keynote in 1965 called for civil rights and integration. In the late 1960s, Alan Watts, James Cone, and Eli Weisel were participating.

Delton Scudder

Delton Scudder loomed large throughout this period. He came to the University from Yale, and throughout much of his 26 years as Chair only hired full-time faculty with Yale Ph.Ds. The apostolic succession included Harry Philpot, Charles McCoy, Austin Creel, and Dick Hiers.

For those who knew him as a teacher, Delton Scudder was universally known as someone who cared deeply about his students’ learning and welfare. Typically, he would appear on campus, cigar in mouth, lugging two heavy, old, battered, leather, suit-case-size briefcases stuffed with charts, lists, and other materials he was going to distribute to the hundred or so students he was about to meet.

Beyond his teaching, Delton functioned as de facto minister to the University in both solemn occasions and times of crisis. Among his files are invocations dedicating new residence halls, prayers at commencement services, and funeral sermons for University Presidents. Two days after the death of John F. Kennedy, Dr. Scudder gave a spell-binding address to a packed Florida Gym that lead the entire University toward an understanding of what had just transpired.

By the mid-1960s, Delton, along with Austin Creel, Dick Hiers and others, had shaped a 12 course curriculum. The original core of this curriculum was the Bible, Religion in American Life, and Comparative Religion, and from there it branched out to Ethics and Philosophy.

The Academic Study of Religion

In his book on The Soul of the American University, George Marsden tells us that during and after the 1960s Protestant academic leaders gradually gave way to secular, non-religious forces that shaped the university largely through a curriculum connected to the larger, market-driven society. What this meant for departments of religion was a separation from their ministerial role, a greater recognition of religious pluralism, and a new effort to justify their existence on the high ground of objective, value-free academic inquiry.

Harbingers of these developments at the University of Florida can be seen in a 1958 Study of the Department directed by Delton Scudder (and with our Advisory Board member Perry Foote as a student member) that made two important recommendations:

1) responsibility for directing religious activities should be moved out of the Department and placed under the Dean of Students,

2) and the Department offices should be moved out of the Union and placed alongside other academic departments.

Gradually these recommendations came into being.

The addition of Austin Creel in 1958 and Richard Hiers in 1961 also anticipated these new developments. Though both Yale men, they had the academic training that Delton lacked in Comparative Religion and Bible, respectively. The addition of Gene Thursby in 1970, from Duke to be sure but also a Protestant minister, further secured the Department’s Asian course offerings.

A number of other faculty passed through the Department during these and later years. These included Thaxton Springfield, Delt’s Methodist minister from across the street, who was a significant presence in the 1950s, and Taylor Scott, who passed away just this last year and taught in the Department until 1980 (See In Remembrance, p. ?). Each of these people and others have contributed to the life of the Department.

Elders

Several of our Department elders, along with others who have supported us, are with us today.

Let’s begin with Austin Creel. Austin’s leadership skills were on display during the 13 years he served as Chair between 1977 and 1990. In 1988, then Dean Charles Sidman praised him for “the nucleus of strength, and of common sense and collegiality, that now permeates the Department.” It is to Austin that we owe the far-sighted creation of the Department’s Advisory Board long before other departments began to move in this direction. And it is to Austin we owe not only the solid foundations for the Department’s Asian curricular offerings, but too the founding in 1973 of the College’s Asian Studies Program. (039) Finally, Austin put us on the road to computerization. A development we welcomed with appropriate rituals and blessings.

Dick Hiers served the Department even longer than Delton or Austin, retiring after more than 40 years in 2003. As many of you know, Dick’s early career was in Bible and Ethics; this expanded in the mid-1980s to the Law. While still teaching in the Department, he was able to get a UF law degree, ranking high in his class, and then served a clerkship to Judge Jerre S. Williams of the United States Court of Appeals’ Fifth Circuit in Austin, Texas. Dick was most known at UF for his tireless work on committees and in the UF Senate where he was a vocal advocate of proper procedures and academic freedom. He was one of the College’s main links to the law school and was a mainstay of the local Phi Beta Kappa chapter. For those of us still in the Department the image of his upright-walk, floppy hat, briefcase in hand, and ready smile can still be seen today.

Also in this late 1960s time period, the Department signaled a significant step toward religious pluralism by hiring Michael Gannon and Barry Mesch.

Michael Gannon, who went on to a distinguished career in administration and in History at the University and has only recently retired, was then Father Gannon, the Newman Center priest. In 1962, Mike completed a history Ph.D. at UF and was subsequently hired into both the Department of Religion and the Department of History. During the late 1960s student protests, he was the strongest moral voice within the University.

In 1969, Barry Mesch was hired from graduate school at Brandeis and, over the next decade, brought the academic study of Judaism to campus. In 1973, Barry founded the Jewish Studies Center and was its Director for ten years. He was instrumental in bringing to our library the core of our world class Judaica collection and initiated the first study abroad program in Israel. As Austin Creel put it, Barry was universally known for his “conscientious attention to matters of student welfare.” There are former students among us today – I think immediately of Fred Chaiken – whose lives were changed through the teaching and counsel of Barry Mesch. Barry left us in the early 1990s to become the Provost at Hebrew College in Brookline, Massachusetts, but he is here today.

By 1970, these six faculty: Scudder, Creel, and Hiers now joined by Gannon, Mesch, and Thursby produced a self-study that is noteworthy for its attention to academic rigor and scholarly publications. The following year, Sam Hill was brought in from the University of North Carolina to Chair the Department. Department memos from the 1970s period forward increasingly concern themselves with faculty grants, publications, and the need to carve out time for research. Service to the University, in the familiar form of participation on committees, continued at full throttle yet the Department’s overtly ministerial duties to the University clearly waned. What remained constant was a focus on the nurture of students within and without the classroom.

This brings me to Sam Hill. If ever there was a church for the study of southern religion, Sam Hill would have his own chapel. Twelve years after retirement from the University of Florida Sam’s work is still the starting point for anyone seeking to delve into this area of study. His Southern Churches in Crisis was a blockbuster, and other important works followed. To switch metaphors, if ever there was an award for itinerancy in bringing the message of the study of southern religion to nearly every college in this vast region and beyond, Sam would get it. By the 1980s, his cv listed more than forty separate addresses and fifteen endowed lectureships.

At the end of his career, Sam devoted his time to the teaching of Ethics to a devoted undergraduate following. When I first came on the faculty, he pulled me aside to say that what we really were doing in our teaching was “character formation.” One could not have found a better mentor in this than Sam.

In 1974, Sam Hill remarked, “ My young colleague, Gene Thursby, is very bright, exceptionally industrious, and keenly committed to his professional work. His research energies and capabilities are prodigious. His teaching performance is also outstanding. His use of innovative teaching materials and techniques is extensive and discriminating.” Throughout his career, Gene has been an outstanding teacher. His use of innovative teaching techniques reached its fruition in this computer age where Gene is subject editor for a variety of Asian religious and new religious movement topics. Google up “Gene Thursby” and away you will go. These last few years, Gene’s scholarship has experienced an unusual flowering with the publication of new books on the Hindu World, Religions of South Asia, and Modern Hinduism.

On a personal note: when I became chair I knew I was going to need some kind of father confessor to whom I could go, not so much to confess my sins – though they are many – but to commiserate with the lunacy that sometimes occurs in administration. Gene has and continues to fill that role for me. I will sorely miss him.

During the 1970s, three other faculty joined the Department through circuitous means and stayed on with us for some time.

In 1969, Harold Stahmer was a Professor of Religion at Barnard College when his interest and activism in the civil rights movement brought him to the University of Florida. As an Associate Dean at UF, Hal played a major role in the integration of the University. He was also instrumental in establishing the Women’s Studies Program, the Center for Jewish Studies, the Center for Gerontological Studies, and the Criminal Justice Program. Following his years in administration, Hal joined the department as a professor of religion and philosophy.

Dennis Owen and Shaya Isenberg came to the Department following the closing of the old University College and the integration of its faculty into departments across the University. Dennis officially became a member of the Department in 1979 and departed in 2000.

As Delton Scudder retired, he passed on several mantles. To Dennis was passed the appetite for teaching literally hundreds of students each semester, advising our undergraduate majors and, in the 1990s, our graduate students as well. Will Setliff is one of our graduates from the 1990s who came all the way from Minnesota to be with us today. As Will told me, “Dr. Owen inspired me to pursue a major in Religion. It wasn’t blatant persuasion, rather it was his passion exhibited by his willingness to spend hours talking with students outside of class that brought to life a perspective within me that the religious experience is a great lens through which to acknowledge, examine, and relate to all aspects of the human condition.”

Like Gene Thursby, Shaya Isenberg is still with us but close to retirement, so I am joining him with this merry band of the 1970s and 1980s. It is worth noting how many times the word “wise” is used to describe Shaya. Especially in his years as Chair and now, with Gene, as Department Elder, Shaya has been a sober, steadying influence bringing insight and compassion to departmental complexities as they have arisen.

Part of Shaya’s legacy will certainly be institutional building. With Barry Mesch he started the Center for Jewish Studies and raised the initial funds for its now glorious library. Way back in 1974, he began, with Sidney Homan in English, a interdisciplinary Presidents’ Scholars Program that is a forerunner of the Honors Program today. The Center for Spirituality and Health could not have reached its current flowering without Shaya’s discernment and energies as Associate Director. And he was a guiding force behind the creation of both our M.A. program in 1990 and our Ph.D. Program in 2003. He too will be sorely missed.

Patout Burns is a superb Augustine scholar who is now the Edward A. Malloy Professor of Catholic Studies at Vanderbilt University. Back in 1985, as the story goes, then Dean Charles Sidman took a look over at the Protestants and Jews in the Religion Department and gave us two positions in Catholicism. Patout and I came to the department as a result of that decision. Patout was to cover the old stuff, I guess, and I was to deal with the new.

In his short time with us, Patout was thrust into administrative responsibilities: serving on the Executive Committee of the Philosophy Department and the College’s new Tenure and Promotion Committee, which Dean Sidman had created. During this time, as Austin has stated, Patout gave “unstintingly of his time and provided fresh perspective and judgment on many matters.”

Toward the Future

If you are following along on a timeline, we are only now around 1988 but we have run out of retired and former faculty who are present, though we still have a couple of others, and we will get to them. If you want to know about the last 15 years or so, here is a brief sketch.

On one hand, that there are marked continuities with the past. Though a great deal has changed in the field of religious studies in the 60 years since Delton Scudder’s original curriculum of Bible, Ethics, Religion in American Life and Comparative Religion was taught (entirely by him), we have continuity today in the biblical field with the efforts of Leo Sandgren, Jim Mueller (when not in the Dean’s Office) and, most recently, Robert Kawashima and Greg Goering. In Ethics, we have Anna Peterson and Bron Taylor. The Religion in American Life mantle has been passed from Delton to Sam and Dennis and now to me. In Comparative Religion, which in Delton’s teaching meant a three-course sequence in first, Hinduism and Islam, second, Buddhism and Chinese religions, and third, Judaism and Christianity, we have had a flowering of new faculty. Next fall, Travis Smith will be joining Vasudha Narayanan in teaching Hinduism. Azim Nanji, our Chair in the early 1990s was hired to teach Islam, as was Richard Foltz (who has departed), leaving Zoharah Simmons to carry that mantle. Jason Neelis and Mario Poceski cover Buddhism and Chinese Religions, while Leah Hochman, Gwynn Kessler and Robert Kawashima have carried forward with Shaya Isenberg the study of Judaism. In broad, these are all continuities with Delt’s original curriculum.

Quite different from the past, on the other hand, is our social make-up. Prior to the hiring of Vasudha Narayanan in 1982, the permanent Department faculty were all white men. And it would be 1993 before another woman would be hired – Anna Peterson. But this social composition was actually on par with other University departments and religion departments across the United States.

One way of looking at departmental hiring over the last ten years is that we have become substantially more diverse. We now number 17 and this includes seven women, three African-Americans, two Asian-Americans, and one Hispanic.

Another new direction has been the development of our doctoral program with its three unique tracks in: the Religions of Asia, Religion and Nature, and Religion in the Americas. In Religion in the Americas, this has meant the hiring of new faculty with exciting new teaching areas, like Robin Wright’s focus on Indigenous Religions, Jalane Schmidt’s expertise in the African Diaspora, Manuel Vasquez’s interests in Globalization and the training of all three in Latin American religions. In Religion and Nature it has meant the creation of a whole new field by ethicists Bron Taylor and Anna Peterson and Hinduism scholar Whitney Sanford. And in Religions of Asia, this has meant a new focus on the transmission and interaction of Asian religions as they move across and beyond Asia.

How this doctoral program came about is a story unto itself, but it could not have happened without the support and encouragement of our Dean Neil Sullivan. By providing us with the funding we needed to attract first-rate graduate students, and to hire faculty in new and innovative areas, Neil made it possible for us to realistically see ourselves as comparable to the best public university religious studies departments (Like North Carolina, Indiana, and Santa Barbara).

Along with Neil Sullivan, we are especially thankful to our Advisory Board. Board members who are present include: Dick Petry, Gene Zimmerman, Perry Foote, Ralph Nicosia, Vernon Swartsell, and Linda Wells.

Like many on our Board members, Linda Wells was a major player in Religion in Life Week when she was an undergraduate and before she went off to law school. When Austin Creel first formed the Board in the 1980s, it was Linda who chaired it and continues to lead us now. Throughout these years and especially since the creation of our Ph.D. program she has supported our efforts to grow and sustain our doctoral program. I want to thank her now for all of us for standing with the department now and in the future.

Perry Foote, as I have mentioned, was the President of the Student Religion Association when he was here as a student and a member of Delton Scudder’s Committee that re-evaluated the Department in the mid-1950s. Perry has had a distinguished career as a doctor here in Gainesville. He has also been a member of the Advisory Board for many years. In recent years Perry has made a commitment to create an endowed chair in Christian Ethics to be known as the Samuel S. Hill Jr. Chair.

Finally, I want especially to thank Cecilia Rodriguez-Armas our business manager, and Annie Newman, our senior secretary, and those who have gone before them in these positions. And then there are our students, old and new, many of whom are here today, who continue to stimulate us.

Toward the end of George Marsden’s book on the Soul of the American University, he observes with approval the decline in the belief that there can be anything like objective, value-free knowledge. Scholars have interpretive perspectives which they bring to their research. I cannot speak for the department here, but I see this as an opportunity for multiple religious and cultural voices to be heard. We will be able to talk about this more tomorrow in the common conversation to be led by John Sommerville.

But let me say this, in my understanding, the religion department today is an increasingly plural environment where we live in overlapping neighborhoods that come together for both immediate and longer-term conversations. Our established fields of research are our neighborhoods, Bible, Jewish Studies, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, African Religions and Indigenous Religions. Yet our neighborhoods also come together not only in our three doctoral tracks of Asia, Nature, and the Americas but also in such areas as Ethics, Gender, and Method and Theory. And our neighborhoods are part of a larger city called religion. Though we may understand the term in different ways, it provides us with our common identity. What is striking today is that, unlike the past, our department has no normative religion, geographic area or method. It is the kind of department that is best equipped to creatively respond and contribute to an understanding of religion as it is lived today.

So we are thankful to each one of you who has come here today, and to the many who are not here, who have contributed great and small to the origins, growth, and development of this department.